How to be green and destroy farmland

- Pat Phillipps

- Mar 12, 2024

- 4 min read

Once upon a time Reading University owned many acres of countryside all round the village of Shinfield. It employed dozens of people who lived locally, working at the National Institute for Research in Dairying, where they improved the quality and efficiency of diary production.

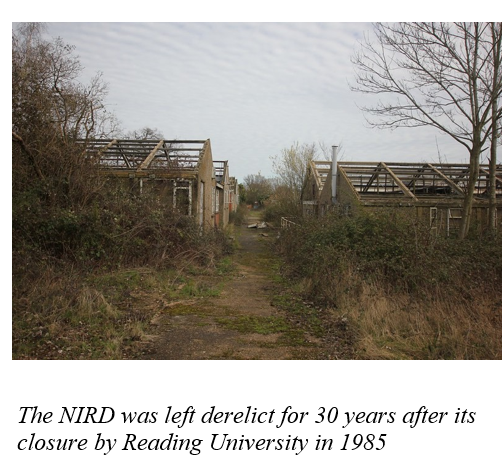

Based on the land, they were green jobs, if you like, and they helped to ensure our food security. But then the University closed the NIRD and relocated its dairy research work to Hall Farm. Gradually it sold off its land around Shinfield to housing developers, covering what had been green farmland with uniform suburban streets and houses.

Now the University is coming for Arborfield. UoR management wants to replace the countryside between Loddon Bridge and Sindlesham with 4,500 dwellings, their driveways and their access roads. As it did with Shinfield, it plans to put hundreds of acres of farmland under concrete. Yet a UoR Pro-Vice-Chancellor could speak in December 2022 of his university's 'significant and sustained efforts to reduce our impact on the environment’, and of its 'ambitions to be one of the greenest universities in the world’. How does a University that boasts its ‘green’ credentials like this come to be destroying green fields on such an industrial scale? Is it just cynical, moneygrubbing self-interest? The University’s many detractors might think so, but there's more to it than that. We have to look at the broader picture and see how their management’s plans align with bigger agendas.

Farming becomes harmful

Reading University once built its reputation on agricultural courses. Students from all over the world came to the University to learn how to improve farming yields and food production.

But times have changed. Since then, a new agenda has taken over, as governments in various countries started to put the squeeze on farmers. Instead of being seen as what the countryside is all about, farming is now in the crosshairs of policies to restrict activities deemed by government-level policy-makers to harm the environment. The government’s strategy for supporting farming actually means, as The Guardian put it in April 2022, ‘Farmers are paid for making environmental improvements, rather than the amount of land they farm’.

This goes higher than national politics. The British government was one of many signing up to the UN 2023 COP climate agenda, which says: ‘Any path to fully achieving the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement [a treaty intended to cap the global average temperature increase] must include agriculture and food systems’. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s goal is to reduce methane emissions by 25% by the end of this decade. That has implications for dairy farming, because methane created in cattle digestive systems is a greenhouse gas. Reading University Professor Keith Shine, a leading member of the UN's IPCC, co-published research in 2017 claiming methane was more significant in climate change than had been thought, not welcome news for dairy farming.

DEFRA targets farming

Farming worries global policy-makers for other reasons. Ammonia and oxides of nitrogen are emitted by manure and fertiliser application - the UN’s 2022 IPCC report recently expressed concern about their increased levels in the atmosphere. On cue, the UK Department for the Environment, Farming and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) 2023 came up with a draft air quality strategy which noted their impact: ‘Action need[s] to be taken in more rural locations - ammonia emissions from farms… contribute to regional levels of [particulate matter] pollution.’ DEFRA wants local authorities to try to get ammonia emissions reduced. It says: ‘Agriculture is the largest source of ammonia… While not having direct regulatory powers over agriculture, local authorities should exercise their wider functions to minimise emissions from this source’ (DEFRA Air quality PM2.5 targets Detailed Evidence Report, May 2022).

So local authorities will be used to carry out Westminster government policy, which is itself being imposed from a higher level. We can no doubt expect WBC to snap to attention and look for ways of doing the government’s bidding. Perhaps council bureaucrats would find it useful to report at some point that ammonia and nitrous oxide emissions have gone down, following the disappearance of dairying at Hall Farm.

The ‘food transition’

Then there’s the agenda for food and farming known as the ‘food transition’, which is bearing down on farmers via government and supranational bodies. The UN’s Environmental Programme favours alternatives to meat and dairy so as to reduce the ‘environmental footprint’ of the current global food system. The Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition, a committee then funded by the British government, briefed the UN's 2021 Food Systems summit saying: 'Policymakers need to adopt a perspective which considers the environmental footprint of all parts of food systems – from farm to fork. This perspective needs to encompass greenhouse gas emissions…’. The following year, the government held a 'Farm to Fork’ summit, where it announced its Sustainable Farming Incentive. This pays farmers for actions they take to manage their land in an environmentally sustainable way: farmers are paid for sustainable farming practices, and creating habitats for nature recovery. growing food and rearing livestock. Under the EU they were paid for the land they farmed and where they grew food, but that’s no longer the priority, it would seem.

What alternatives?

Unsurprisingly, many farmers see the writing on the wall for agriculture as they have known it, and they’ve been selling up. Over 40% of British farms sold in recent years were purchased by

non-farming buyers, including multi-national investment companies.

In this context, it should come as no surprise either that Reading University doesn’t wish to keep its farmland. It wants instead to be at the forefront of influential ecological trends that favour new approaches to farming and food.

We at the SOLVE campaign must acknowledge there are powerful forces at work which question the sustainability of agriculture astraditionally understood, and what this implies for the future of the Hall Farm site. That is why, two years ago, we submitted to the University a carefully detailed document suggesting a wide range of environmentally-friendly alternatives to building 4,500 houses on farmland

(https://www.green4grow.org/_files/ugd/7f3f74_49ddc05fc1804b4192d7789ddf9177d6.pdf). We hoped the country’s fourth-greenest university would be interested, but… we’re not sure.

Pat Phillipps

Comments